Malicious Perspectives

Calculated distortions: why we're vulnerable, how to spot them, and what to do about them.

Calculated Distortions And Their Consequences

What happens when viewpoints aren’t just misguided, but deliberately poisonous? The answer begins with acknowledging a basic truth about perspectives - their partiality. ‘Partial’ means localized, limited, and incomplete. This partiality isn’t a flaw, but a fundamental feature of how we engage with reality through these vantage points. While we might aspire to ‘a view from nowhere’, what we actually occupy is a ‘view from within’. For our sensemaking is always situated within a particular body, culture, and historical moment that shapes what we see. And while we can certainly step back from these lived orientations, we can’t step outside of them entirely. Which means that perspectives necessarily reveal and distort - capturing some aspects of a situation while obscuring others.

High-quality perspectives acknowledge these constraints and work within them. Misguided ones ignore or deny them. And malicious ones weaponize them. A malicious perspective is a calculated distortion of reality - one that’s deployed in service of goals its architects dare not state openly. The harm they cause isn’t an unintended byproduct, but a deliberate strategy for achieving ends that honest methods can’t reach. If you have a rotten agenda that would be rejected if stated plainly - and lack the means to impose it through brute force - then manipulation is what’s left. From run-of-the-mill con artists to aspiring dictators, where there’s an incentive and a means, bad actors will use any opening they can find to push their schemes. Hitler, after all, had far more success overthrowing democracy from within than by storming it from without through a putsch. The scale varies, but the pattern doesn’t. So what do these malignant operations look like on the ground?

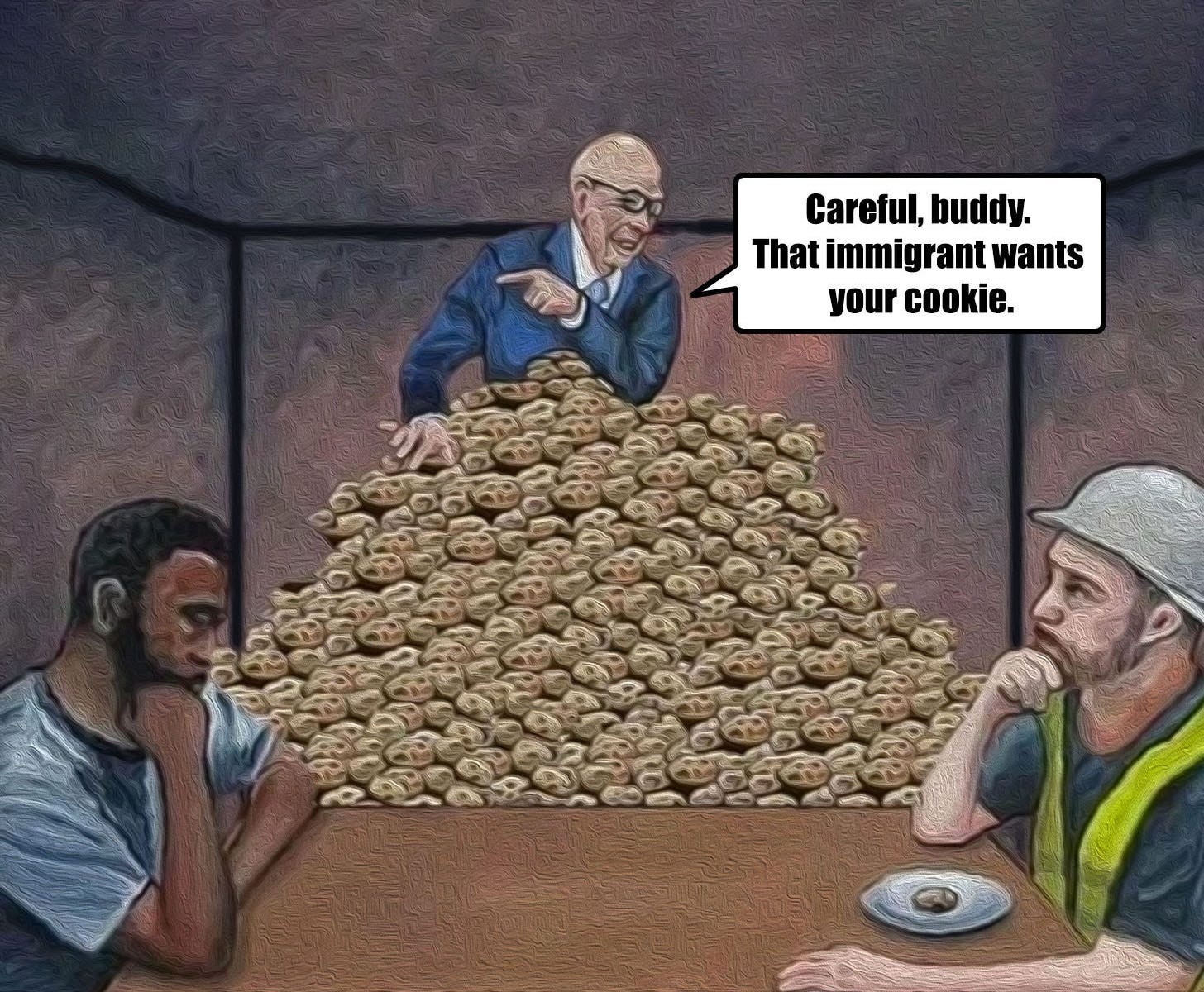

Whether the aim is to deflect accountability, obstruct solutions, or consolidate power, the overall arc of this calculated deception remains the same: exploit problems where they exist, manufacture them where they don’t. And above all, ensure that nothing gets solved, because the goal isn’t to fix anything - it’s to consolidate power, deflect blame, or line pockets. And nothing opens doors to these ambitions like a good crisis. An exploitative employer doesn’t want you to feel secure at your job - they want workers whose positions are too precarious to make demands. A demagogue doesn’t want kitchen-table issues addressed - they want a citizenry desperate enough to grant them emergency powers.

If this playbook sounds familiar, there’s a reason - it bears more than a passing resemblance to an abusive relationship. Like an abusive partner, pushers of malicious perspectives will: 1) Reel you in with flattery, validation, and belonging. 2) Gradually distort your perception of reality. 3) Exploit your emotional vulnerabilities for control. 4) Attempt to isolate you from outside perspectives that might break the spell.

That’s the playbook. But what makes these manipulative tactics viable in the first place? After all, nobody sets out to join a cult, become a mouthpiece for propaganda, or get swindled by a demagogue. Yet people fall for this stuff all the time, so what gives?

Social Animals In A Messy World

The answer is that we’re navigating inherently murky terrain as social animals who are permeable to influence, with skin in the game for the conclusions we reach. Human intelligence is innately social - the same factors that allow for culture and cooperation also enable manipulation. But how does this play out in practice?

Benefit of the doubt gives these malicious framings an initial foothold, and the permeability of our situated perspectives gives them traction. Our viewpoints don’t emerge from some pristine inner sanctum, but from our messy entanglement with the world. We do our meaning-making as social animals - inheriting cultural templates and adapting or inverting them to fit our circumstances. And critically, this process is thoroughly entangled with our emotions, identity, and social belonging.

Given these stakes, the bulk of our attitudes and beliefs aren’t the product of careful reasoning - they’re organic outgrowths of the lives we’ve lived. We can’t deliberate over everything, so this autopilot is an essential feature of how we navigate the world. Our intellect is mostly content to step in when this pre-reflective flow hits a snag. Reasoning does play a role in this process - just not the leading one. The star of this show is intuition, with intellect acting more like a public relations firm for these emotionally grounded judgments. Reason’s primary job is to rationalize our existing beliefs - reconsidering them is secondary. There’s considerable inertia to revising convictions that we’ve already staked out - which is why it’s usually much easier to dig in than to change course.

Changing our minds is of course possible - it’s just that the path of least resistance runs in the opposite direction. Self-examination is hard, while self-justification runs on autopilot. Which is why we don’t tend to do it until the world knocks us on our ass in a way that our typical defenses can’t cover. But before we get too hard on ourselves, it’s worth understanding why we’re swimming upstream in the first place.

If these shortcuts seem pointless, that’s because we forget that they’re actually adaptations. However much we assume that our minds are built for rationality, evolution had different priorities - namely, keeping us alive. And because there’s no designer driving this process, the solutions it arrives at can be inelegant. In short: evolution doesn’t optimize - it satisfices - settling on adaptations that are ‘good enough’ for survival and reproduction. We see fingerprints of this process in our psychology, which is wired for speed and efficiency over accuracy and precision. The proof is in what we don’t notice. Consider the countless tasks you’ve executed flawlessly today - from getting dressed to eating breakfast to scrolling and tapping while on the toilet - without a moment’s thought.

We conduct most routine activities on autopilot, and there’s a good reason for this - we’d grind to a halt if we were forced to deliberate over the thousands of micro-decisions we make on a daily basis. Careful deliberation is cognitively and emotionally taxing because stopping to deliberate carries real opportunity costs. So it pays to be strategic about what we question - and this selectivity is intertwined with our deeply social nature.

While there’s a modern myth that our ancestors were rugged individualists who survived on grit and self-reliance, the reality was exactly the opposite - for most of human history, being cast out from the group meant certain death. The equation was brutally simple: ‘together we are safe, alone we die’.

That ‘together’, however, was radically smaller than today’s sprawling anonymity. Living in a ‘society’ of millions would have been an unthinkable contradiction for our distant ancestors, who survived within a hostile world by trusting and depending upon a small, tight-knit group. Dozens of individuals at most, whose survival was inseparable from your own. When your entire social universe is small enough to fit around a fire, reputation and belonging aren’t vanity but essential for survival.

This ancestral legacy has carved deep grooves into our psychology that continue to color our intuitions to this day. We are, fundamentally, groupish creatures. That means we’re calibrated for in-group loyalty over impartial judgement, and sensitivity to our social status over merit-based assessment. And these instincts run deep - operating at an intuitive level that’s scaffolded by reason and reinforced by emotion.

The practical takeaway is that we’re wired to trust what feels familiar, fear what feels foreign, conform to the group, and accept simple explanations over complex ones. This creates predictable vulnerabilities that skilled manipulators know how to exploit. And the most effective means for doing so often isn’t through lies. Lies are a liability - they take effort to maintain, leave trails investigators can follow, can collapse under their own contradictions. What’s better by far is to manufacture an unreality where truth itself is beside the point. Which brings us to the realm of bullshit.

Flooding The Zone

Bullshit is speech that’s manufactured without any regard for truth or falsehood, where the real aim isn’t to persuade, but to overwhelm and distract in pursuit of an undisclosed agenda. Bad actors are drawn to it like flies to shit because it’s a remarkably effective scaffolding for propping up a rotten edifice. This is how malicious perspectives gain their deepest foothold - not through convincing arguments, but by flooding the zone with shit until people give up trying to separate fact from fiction. It’s a deliberate scorched earth campaign against the epistemic commons, corroding trust in the type of shared reality that allows for productive disagreements.

And when bullshit is deployed at a societal scale, it becomes something even more dangerous - what scholars of authoritarianism call The Big Lie. Not an isolated falsehood - like denying an affair or fabricating evidence for weapons of mass destruction - but a narrative so audacious and repetitive that it wears down the mind’s ability to resist.

History’s Most Consequential Lie

What happens when these audacious unrealities gain purchase? They draw blood. They build gas chambers. They turn neighbors against one another until societies fracture along lines of manufactured hatred. In short, they don’t just distort our understanding - they pave the way for real-world violence.

We don’t have to speculate about this dynamic - the historical record offers no shortage of case studies. From The Protocols Of The Elders Of Zion that fueled pogroms across Europe to the Lost Cause narrative that paved the way for Jim Crow, the examples are as familiar as they are horrifying. Yet there’s one that towers above the rest as perhaps the definitive example of the Big Lie. The story begins in the final months of World War 1, in a war-ravaged Germany facing imminent defeat and collapse.

After four years of brutal conflict that had sent two million Germans to their graves and a naval blockade that left millions more on the brink of starvation, the military dictatorship that had emerged over the course of the war could no longer deny the reality that was staring them in the face. With its armies on the brink of collapse and civilian unrest escalating towards revolution, Germany faced a stark choice - surrender immediately or face imminent invasion and inevitable occupation by the Allied Powers. The Schlieffen Plan - Germany’s blueprint to avoid a two-front war by delivering a swift knockout blow to France - had failed catastrophically in the opening months of the war, condemning Germany to the grinding war of attrition the plan was designed to prevent.

With Allied armies pressing in on all sides, the generals who had promised swift victory now confronted total defeat after four years of industrial-scale carnage that had bled the nation white. This wasn’t just a bitter pill to swallow - it was a social apocalypse for the military aristocracy that had driven their nation to ruin. The toll on Germany’s civilian population, which had endured years of deprivation while their husbands, sons, and brothers died in trenches was similarly catastrophic - creating a traumatized nation that was desperate for answers, but would settle for scapegoats.

It was within this volatile environment that the architects of this defeat concocted a scheme to evade accountability for the catastrophe they’d engineered. The solution was to shift the blame to the newly formed civilian government, which had been hastily assembled as a prerequisite for a negotiated peace with the Allies. Rather than signing their names to the humiliating peace they’d made inevitable, Germany’s military elite instead engineered a transfer of power that left civilians holding the bag for a military disaster whose true scale had been systematically concealed from the public. Unless you were an exceptionally imaginative or unusually well-informed civilian, the sudden declaration of defeat would have arrived as an incomprehensible shock. While soldiers in the trenches had no illusions about Germany’s dire situation, those on the homefront were kept in the dark through strict censorship and wartime propaganda that assured them that victory was around the corner. Adding to this veneer of plausibility was the fact that Allied troops had yet to set foot on German soil, its armies still occupied foreign territory, and no climactic battle had sealed Germany’s fate.

It was into this perfect storm of shock, grief, and manufactured ignorance that Germany’s military elite orchestrated their coup de grâce - a Big Lie that would become the founding mythology of Nazi ideology, reshape German politics into a cauldron of conspiratorial grievance and betrayal, and open a path for decades of dehumanization that would ultimately lead to the Holocaust. The Dolchstoßlegende, or the Stabbed-In-The-Back myth, held that Germany wasn’t defeated from without; it was betrayed from within by Jews, socialists, and democratic politicians. While all three groups were vilified, antisemitism was the beating heart of this Big Lie. One where Jews were cast as the enemy from within - never mind that thousands of German Jews had died in trenches trying to prove their loyalty to a nation that would turn on them.

While the Stabbed-In-The-Back myth stands as history’s most consequential Big Lie, the technique didn’t die with the Third Reich. Its malevolent logic has been a tried-and-tested tactic of authoritarians ever since: bury the truth beneath a mountain of audacious bullshit until reality itself is contorted into something unrecognizable. Variations of the Big Lie have motivated state sponsored violence from Jim Crow era lynchings to the Rwandan Genocide to the January 6th attack on the US Capitol. The tactics differ, but the thrust remains the same - to give malicious actors carte blanche to consolidate power, persecute enemies, and destroy lives.

Brutal stuff - but history, real history - doesn’t pull any punches. Likewise, epistemology is never just academic - it has consequences that can be measured in body counts. When done well and honestly, both should make us uncomfortable.

Architects, Opportunists, and Absorbers

Let’s pause here for a moment, and take a needed breather.

We just covered some HEAVY material - from evolutionary psychology to our susceptibility to bullshit to the Big Lie that enabled the Holocaust. So stretch your legs, grab a snack, give your cat or doggo a boop on the nose. When you’re ready, we’ll tackle the practical stuff: how to spot these deceptions early, what to do when we encounter them. And crucially, how to prevent this framework for combatting malicious perspectives from being used maliciously.

Breather taken? Excellent. Now for the practical toolkit.

One crucial caveat before we get to the diagnostics: we’re identifying potentially malicious perspectives. ‘Potentially’ being the operative word here, since malicious viewpoints don’t announce themselves as such. This is complicated by the inherent fuzziness of the boundary between unwitting mistake and willful manipulation. The line blurs in both directions - not everyone who amplifies a malicious perspective does so maliciously, and not everyone who gets it wrong has made an honest mistake. Most ignorance is unintentional, but some is cultivated. Most blind spots are genuine, but some omissions are strategic. Most errors stem from bias, but some ‘mistakes’ serve agendas. The point being, both camps exist on a spectrum: calculating architects at one end, unconscious absorbers at the other, with opportunists of various stripes occupying the space between.

If all this sounds confusing, recall our earlier point about the permeability of our perspectives. We absorb and adapt viewpoints without necessarily grasping where they came from or what they’re designed to accomplish. To return to our case study, there can be zero doubt that Germany’s military leaders knew what they were doing when they fabricated their Stabbed-In-The-Back myth. But the story isn’t so simple for the traumatized people who amplified it. Some - Hitler, Goebbels, ‘blood and soil’ demagogues - pounced on the chance to fracture society along lines of manufactured hatred. Far more simply believed what they’d absorbed through cultural osmosis, their acceptance eased by antisemitic prejudices that made them easy marks for this calculated deception.

And if this latter group had Jewish neighbors, coworkers, and even friends - people whose shops they frequented, whose children attended the same school - many managed the mental gymnastics necessary to look the other way as those neighbors were stripped of their rights, property, and eventually - their lives.

So does the difficulty of pinning down malicious intent mean that unconscious absorbers get a free pass? Not at all, but it does mean that we need different approaches for different positions on this spectrum. The person parroting racist talking points they absorbed from Fox News isn’t the same as Tucker Carlson - they need pushback, not a tribunal. Likewise, Tucker doesn’t need a reality check - he needs public exposure and accountability for the poison he’s deliberately spreading. The name of the game is proportionality - applying situationally appropriate responses that scale with culpability.

The Five Fingerprints Of Malice

With that crucial caveat nailed down, let’s roll out the diagnostics: the five ‘fingerprints’ of malicious perspectives. To illustrate each fingerprint, we’ll be sticking with the Nazis as our example. Why? Because they’re the prime inheritors of our case study. They hit all five fingerprints with unusual clarity. And - let’s be honest - if your diagnostics can’t identify Nazism as malicious, it’s not worth the paper it’s printed on.

So without further ado, here’s what to look for.

1) Strategic Inconsistency - Being opportunistic rather than principled. This may take the form of standards that are fiercely enforced against an out-group, while being quietly shelved for an in-group. Or it may look like loudly touted principles that are discarded the moment they become inconvenient.

Real-world example: In the early 1930s, Nazi brownshirts would deliberately provoke street brawls with communists and social democrats, then rage about Leftist violence. Law, for the Nazis, existed to protect their group without limits, and limit their enemies without protection.

“Law and order for thee, not for me.”

2) Disproportionate Targeting - Punching down rather than up. Malicious perspectives direct their ire at communities who aren’t in a position to fight back. All while giving the powerful and well-connected a pass, or actively running interference for them.Real-world example: Jews comprised less than %1 of Germany’s population, yet they were painted as an existential threat to the nation. The sacrifices of Jewish war veterans were systematically erased, while the Beer Hall Putsch insurrectionists who tried to overthrow the democratic government were treated as patriots.

“Scorn for the defenseless, tears for the powerful.”

3) Performative Provocation - Inciting outrage as a form of manipulation. This isn’t about making controversial arguments - it’s about using emotion to bypass rational evaluation altogether. Shutting down critical thought isn’t a side effect of this provocation, it’s the entire point.Real-world example: When SA stormtrooper Horst Wessel was killed in 1930 during a dispute with his landlord over unpaid rent, the Nazis transformed him into a martyr through relentless propaganda. The “Horst Wessel Song” became the Nazi anthem, turning a street thug’s squalid death into a sacred sacrifice.

“Action over reflection, spectacle over truth.”

4) Crisis Fabrication - This is the art of making mountains out of molehills - or, more precisely, mountains out of mirages. Take something that’s either not happening, happening at trivial scale, or not actually a problem, and inflate it into an existential threat requiring the normal rulebook to be thrown out.

Real-world example: The burning of the Reichstag - the German parliament building - by a lone arsonist in 1933 gave Hitler his pretext for a set of emergency decrees which dismantled Constitutional democracy in Germany.

“Never let a good crisis go to waste.”

5) Selective Epistemic Rigor - Demanding extraordinary standards of proof for established facts, while accepting flimsy evidence for extraordinary claims. This fingerprint cloaks itself in the language of skepticism while inverting its actual practice.Real-world example: The Nazis gobbled up conspiracy theories like kids in a candy store, while dismissing international scientific consensus for Relativity Theory as ‘Jewish science’.

“Reject established facts, double down on the absurd.”

So those are the markers. Yet it’s worth remembering that these fingerprints are a diagnostic tool, not a magic wand. They help us identify patterns that warrant scrutiny, but they’re not a replacement for understanding context, motivation, and stakes. Which raises the obvious question: once we’ve identified a malicious perspective, what’s an appropriate response?

Why Good Ideas Don’t (Necessarily) Outcompete Bad Ones

Here’s what we don’t do - assume that malicious ideas will inevitably wither and die when exposed to rational critique. Malicious bullshit loves rational critique - the very act of treating it seriously allows it to masquerade as legitimate viewpoints worthy of consideration. Inclusivity - the notion that we should accommodate different ideas and viewpoints - is a worthy ideal that’s self-undermining without proper guardrails. Bad actors weaponize this openness to normalize all manner of cruelty and deceit under the guise of civility: “I’m just asking questions” or “you have your perspective, I have mine.”

Unfortunately, malicious perspectives have an unwitting ally in a widely held theory of information, sometimes expressed as ‘The Marketplace Of Ideas’. The naive assumption is that bad ideas, like bad products, will inevitably lose to better alternatives. On the surface this is sensible - when everyone is participating in a reasonable approximation of good faith, dialogue and scrutiny really can move us towards better answers. When expanded from an ideal to an expectation, however, it becomes a dangerously ahistorical myth. For a definitive refutation of this myth, let’s turn one last time to our case study.

In the years before Hitler seized power, his ambitions were plainly visible to anyone paying attention. These weren’t subtle dog whistles but explicit declarations of intent. Prominent intellectuals and journalists recognized these ideas for what they were - hateful, absurd, and dangerous. Weimar Germany was a progressive democracy with a robust civil society where the marketplace of ideas was functioning exactly as the naive view would expect: bad ideas were being challenged by better ones. Yet this marketplace catastrophically failed to prevent the Nazi’s rise to power. The lesson is sobering - malicious perspectives don’t always lose when in open competition with truth.

The fatal flaw of the naive view is twofold. 1) It wrongly assumes that people are, for the most part, rational actors who care about truth - when everyday experience consistently reminds us that this is often not the case. Perspectives aren’t just intellectual propositions, they serve deeply emotional needs that are often at odds with the truth. 2) It wrongly assumes that sense and nonsense are competing on an even playing field. They rarely are. Truth requires evidence, consistency, and good faith. Bullshit requires none of these - it can be manufactured at will, changed on the fly, and deployed faster than it can be debunked. The marketplace metaphor breaks down when only one side is attempting to have an honest discourse.

The Toolkit: Exposure, Accountability, Defiance

So if the Marketplace Of Ideas can’t be relied upon to defeat malicious perspectives, what types of responses are actually effective? We’ve already seen the consequences of trying to engage with manipulation tactics as if they’re legitimate perspectives. But equally misguided are attempts to control malicious viewpoints through censorship. For suppression hands malicious actors exactly what they want: victim status and increased attention. Just as we can prosecute criminals without violating due process, we can disempower malicious perspectives without sacrificing freedom of speech. (Private platforms enforcing terms of service against harassment and calls to violence is a different matter from state censorship).

Instead of legitimizing them through engagement or empowering them through suppression, the smart move is exposure and accountability. Exposure means drawing attention to their hidden agendas, documenting the harm they cause, and demonstrating how they manipulate and deceive. And accountability means ensuring that there are real costs - reputational, political, financial - for the damage they inflict. And often, the sharpest tool for draining them of their power isn’t refutation - it’s ridicule.

Mockery imposes social costs for spreading dangerous nonsense and punctures the false authority that gives them traction. Malicious perspectives thrive on being taken seriously - ridicule denies them that oxygen. It becomes much harder to recruit people to a cause when joining makes you a punchline. Yet there are limits to this approach. Mocking a Nazi in 1930 deflates their pretensions of self-importance and inevitability. Mocking one in 1940 may get you killed. So what do we do when

malicious actors have seized the levers of power?

When the guardrails have failed and malicious actors command the power to punish, the response shifts from prevention to preservation and defiance. Document the harm. Highlight the corruption. Preserve accurate records. Protect the vulnerable. Build alternative networks. Fight back with whatever means are at your disposal, whether that’s small acts of noncooperation or large campaigns of organized resistance. The goal isn’t to reach the hearts and minds of those who are benefiting from the harm they’re causing. It’s resilience, memory, and resistance. Much of which goes beyond the domain of epistemology, but every bit of it hinges on maintaining truth and pushing for conditions that allow it to matter again.

Essential Safeguards - Show Your Receipts, Pick Your Battles, Don’t Be a Hypocrite

One final point, but an essential one. These means we’ve outlined - exposure, mockery, defiance - are powerful tools. Which makes them dangerous. Any idea that’s useful can be used badly - just ask Jesus or the Founding Fathers or Charles Darwin (hello, eugenics), who’d recoil over what’s been done in their names. So how do we prevent a framework for combatting malicious perspectives from being used maliciously?

Here’s three essential safeguards:

Show your receipts. Be prepared to show documented lies, clear conflicts of interest, and patterns of abusive behavior. In short, don’t lob accusations without first doing your homework.

Pick your battles. Not every bad idea is worth going to war over. The vast majority bubble up, get some attention, then fade away without setting the world on fire. Reserve the ‘malicious perspectives’ label for stuff that ruins lives and gets people killed.

Don’t be a hypocrite. Apply the same diagnostic rigor to perspectives you agree with. If you can’t find inconsistencies, hypocrisy, or bad faith on your own side, odds are that you have a blind spot. Be honest about your own stakes and tribal loyalties.

Up Next: So You Say You Want A Theory Of Everything?

These safeguards matter because malicious perspectives exploit our hunger for simple answers to complex questions. But what of the opposite: perspectives that offer complex answers to complex questions? Is the solution to our messy, partial perspectives just a matter of embracing ever more sophisticated maps?

It helps. Nuance lets us map the territory with a greater degree of skill and precision - but it doesn’t eliminate uncertainty. And therein lies a deeper temptation: the dream of a framework so sophisticated, so comprehensive, that uncertainty itself could finally be conquered. Which brings us to our final stop: the search for a master key - not just a theory, but a Theory Of Everything.