The Situated Self

That's right, the 'Self'. We have one, and it matters. Here's what it means for sensemaking.

Do we choose our perspectives, or do they choose us? Once we turn from a ‘view from nowhere’ to a ‘view from within’, this question becomes pointedly relevant. If this sounds like some minor shift, think again. It’s the difference between trying to escape our lived perspective to embracing it as a starting point for inquiry. The pivot isn’t just academic - it carries practical consequences for how we hold our own viewpoints and engage with the viewpoints of others.

This reorientation cuts across the traditional image of philosophy as posing BIG questions about Life, The Universe, and Everything. And it cuts across its mirror image as a discipline of academic morlocks, splitting hairs over abstract nonsense with no bearing on daily life. When we shift our focus from what Reality is to how Reality is experienced, we can pursue meaningful answers to our inquiries, while remaining honest about our motivations for asking.

The dirty secret is that we engage with perspectives Self-ishly. That’s right, ‘Self’. We have one, and it matters. But don’t get it twisted - this isn’t an invitation to take a page from Ayn Rand and pull up the ladder behind us, nor is it a Nietzschean call to trample over others in pursuit of our goals. Rather, it’s a straightforward recognition of our partiality. The world itself is constitutive of who and what you are, but you are not the whole universe. The upshot of this more limited scope? A more expansive ‘Self’ than you might think - not the center of Reality, but a sublime co-creator of one corner of it.

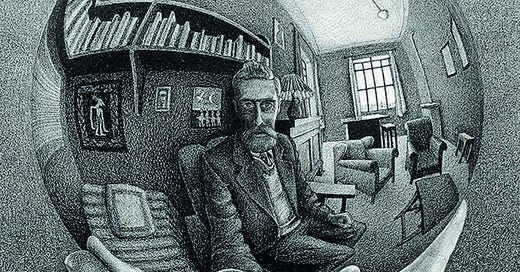

So what does it mean to be one such co-author? It’s a dance of apparent contradictions - dualities which dissolve into productive tension when we inhabit them skillfully. Such a ‘Self’ is localized but permeable. Embodied yet expansive. Embedded in a world we didn’t choose, yet invested in its outcomes. Not spectators to our own existence, but co-participants with ‘skin in the game’ for how things unfold. Put simply: we are a Situated Self - our capacity for Care radiates outwards from where we stand in relation to the world. Situated, but not alone - for we are situated with others. Our individuality is relational - emerging through our concernful involvement with the world, and enacted through everyday practices and activities. In sum: we co-author not as islands or even archipelagoes, but as intersecting biomes within a shared ecosystem.

The Situated Self. Take a moment to let that sink in. Now here’s what it means in practice.

For starters, we enter this inquiry deeply entangled with the phenomena we wish to investigate. For perspectives aren’t merely a set of beliefs - they’re lived orientations. The upshot? We don’t just hold viewpoints, we inhabit them. How much ‘choice’ we have in this inhabitation is precisely the question, but one thing is certain: we don’t leave our viewpoints behind as we examine their construction. So where does this leave us as inspectors? We proceed not as detached theorists, but as engaged practitioners working towards specific outcomes. Our goal? To become more skillful navigators of perspective itself.

With this in mind, let’s return to our original question: do we choose our perspectives, or do they choose us? At first glance, this might sound like a rehash of the free-will debate - that same tired choice versus determinism routine - dressed up in the language of perspectives. Were that the case, we would indeed be beating a very dead horse. The conundrum of whether our actions are freely-willed or pre-determined has been a hobby horse of philosophy since at least the time of Aristotle. A long lineage of smart people have been battling this one out for centuries, with no clear resolution in sight. In the meantime the empirical fields moved on, not much bothered by the impasse. While philosophy was splitting hairs over this self-imposed dilemma, psychology and neuroscience were busy mapping the machinery of human behavior.

The impulses driving this tug of war between free-will and determinism would have been better served by asking whether the question itself leads anywhere useful. The staleness of the conundrum stems from forcing a crude binary upon a lived reality that refuses to be carved up so neatly.

Long centuries spent refining this forced-conundrum, and what’s the payoff? Increasingly elegant solutions to the wrong problem, while the world moves on without you. While philosophy was spinning its wheels science picked a side, contributing to a widening divide between the two disciplines. The cost of this split was subtle but decisive, as philosophy’s pronouncements came to carry less and less weight against mounting scientific evidence. Philosophy could have found a new niche within this shifting landscape as an interpreter for what these empirical findings mean for living, breathing humans. Instead, it dug in its heels, stubbornly insisting on solving the puzzle of human nature from first principles. The result has been a jarring and awkward gap between science and lived experience - where the former points towards determinism while the latter screams choice.

We can - and must - do better than this. Science is the voice of authority in our culture, but it’s not self-interpreting. It has an important role to play in understanding human behavior, but it can’t make meaning from its own findings. What’s needed is a bridge between our scientific models and our concernful absorption in the world that makes its insights meaningful.

Building such a bridge means moving beyond the dualistic thinking that got us into this conundrum in the first place. So rather than forcing a black-and-white template onto a full-color Reality, let’s try a different approach that’s informed by our understanding of the Situated Self. If we can hone in on what’s at stake for us when we ask whether our perspectives are chosen or imposed, we can reframe the inquiry around our actual concerns.

These stakes aren’t theoretical; they jump to the forefront when we feel stuck in self-limiting patterns and ask whether change is possible. They’re present when we recognize that others are doing the best they can, but we still need them to do better. They surface when we see young men getting pulled into toxic ideologies, while recognizing the predatory forces that exploit their insecurities and frustrations. In these cases we’re not detached observers, but people whose lives are entangled with the outcomes. When we’re coping with the messy complexities of the real world, what’s needed aren’t definitive answers but situated wisdom for navigating complex human realities.

Here’s the reframe: agency is real; but so are constraints. It’s not a matter of either/or, but acknowledging that both are a matter of degree. The question, then, is how to carve out avenues for agency within constraints. This means getting clear on which perspectives are an authentic reflection of our values, which we’ve slid into out of manipulation or bias, and which are unavoidable outcomes of the contexts we’re embedded in.